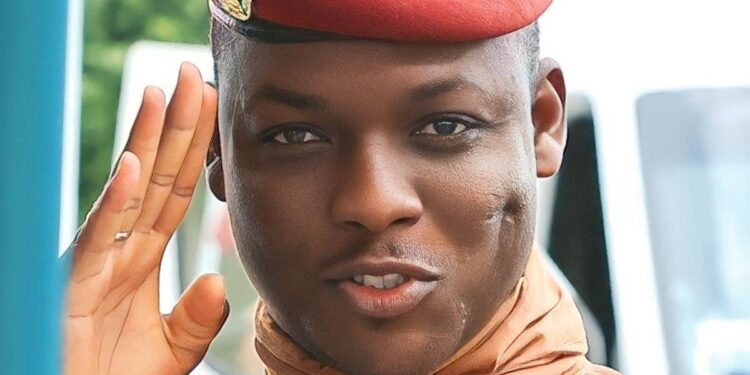

At the forefront of this change is Burkina Faso’s young leader, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, a figure who inspires both fervent support and intense scrutiny. Recent attempts to cast Traoré as a destabilizing force mirror the propaganda that once paved the way for the West’s intervention in Libya against Muammar Gaddafi. But the lessons of that era have not been forgotten, and the West’s outdated tactics are faltering in the face of an awakened, information-savvy Africa.

The scars of Libya’s destruction run deep. In 2011, NATO’s intervention, marketed as a “responsibility to protect” civilian protesters, shattered a nation and left it in chaos. The campaign hinged on vilifying Gaddafi as a dictator, overshadowing his efforts toward African unity and economic autonomy. Many Africans, initially swayed by Western media, later witnessed the devastating fallout—warlordism, human trafficking, and a destabilized Sahel. The betrayal was a harsh teacher: the West’s humanitarian rhetoric often cloaks resource-driven motives.

Today, similar tactics are being aimed at Traoré. U.S. Senate allegations, such as claims he’s misusing Burkina Faso’s gold reserves, smack of a smear campaign designed to undermine a leader prioritizing national sovereignty. Yet, unlike the Gaddafi era, these efforts are meeting fierce pushback. South Africa’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) have denounced such claims as imperialist schemes to weaken a pro-African leader. Across social media, voices are amplifying this defiance, warning that the West is trying to “pull another Gaddafi” by targeting Traoré for his bold stance.

What’s different now? The rise of the information age. Africans are no longer passive recipients of Western narratives. From Ouagadougou to Nairobi, people are tapping into unfiltered perspectives on social media, where discussions of Traoré’s reforms—free education, agricultural progress, and expanded electricity—drown out the West’s vilification. This groundswell of awareness has rendered the old “dictator” label toothless, even against less popular figures like Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni or Nigeria’s Bola Tinubu. For Traoré, often likened to Burkina Faso’s revolutionary hero Thomas Sankara, the narrative is even harder to sell.

The West’s strategy has long rested on two pillars: a compliant global consensus and a coalition of allies. The U.S., despite its military dominance, rarely acts unilaterally. It relies on NATO partners, Japan, South Korea, and a symphony of media outlets to legitimize its interventions. Without this coalition—often dubbed the “oyibo gang” on social media—the empire hesitates. Libya was a textbook example: NATO’s alliance, backed by a media blitz, created the illusion of a moral crusade. But today, with African nations like Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger forming the Alliance of Sahel States and aligning with Russia, the West’s ability to muster such coalitions is eroding.

Traoré’s Burkina Faso embodies this shift. Since his 2022 coup, he has severed ties with France, expelled French diplomats, and embraced Russian military support to fight Islamist insurgents. His defiance of Western dictates, paired with domestic reforms, has earned him a devoted following, making external intervention a political minefield. As one social media user declared, “Africa shouldn’t let whatever happened to Gaddafi repeat itself.” This sentiment captures a broader truth: Africans are increasingly unwilling to endorse narratives that serve foreign interests.

This refusal is the West’s Achilles’ heel. The U.S. empire, for all its bravado, thrives on scripted victories. It crafts pretexts to target weaker nations but recoils when met with unified resistance or a lack of global support. In Traoré’s case, the absence of a pliable African audience and growing skepticism of Western motives have neutered the old playbook. Efforts to suppress dissenting voices on social media, as some users allege, are a weak counter to a tide of awareness no algorithm can halt.

The stakes are monumental. As African nations assert their agency, the West faces a future where its influence is no longer unchallenged. Traoré, whether he triumphs or falters, represents a new breed of leaders who reject subservience. His journey underscores that sovereignty is not just about controlling resources but about owning the narrative. In this era, the empire’s greatest weapon—its ability to shape global perception—is losing its edge. For Africa, that’s the most promising news of all.

Credits: David Hundeyin